- AMD Community

- Blogs

- Instinct Accelerators

- The Potential Disruptiveness of AMD’s Open Source ...

The Potential Disruptiveness of AMD’s Open Source Deep Learning Strategy

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

[Originally posted on 04/03/17]

When a company starts using disruptive technology or a disruptive business model, the results can be spectacular and can leave the competition eating dust.

The reason for this is that although the company’s growth seems linear at first, it eventually reveals itself as being exponential. When a company reaches this point, it becomes very difficult, if not impossible, for competitors to catch up.

This article explores AMD’s open source deep learning strategy and explains the benefits of AMD’s ROCm initiative to accelerating deep learning development. It asks if AMD’s competitors need to be concerned with the disruptive nature of what AMD is doing.

On Deep Learning

Deep learning (DL) is a technology that is as revolutionary as the Internet and mobile computing that came before it. One author found it so revolutionary that he described it as “The Last Invention of Man” [KHAT] – strong words indeed!

Currently, the revival of interest in all things “Artificial Intelligence” (AI) is primarily due to the spectacular results achieved with deep learning research. I must however emphasize that this revival is not due to other classical AI technologies like expert systems, semantic knowledge bases, logic programming or Bayesian systems. Most of classical AI has not changed much, if any, in the last 5 years. The recent quantum leap has solely been driven by deep learning successes.

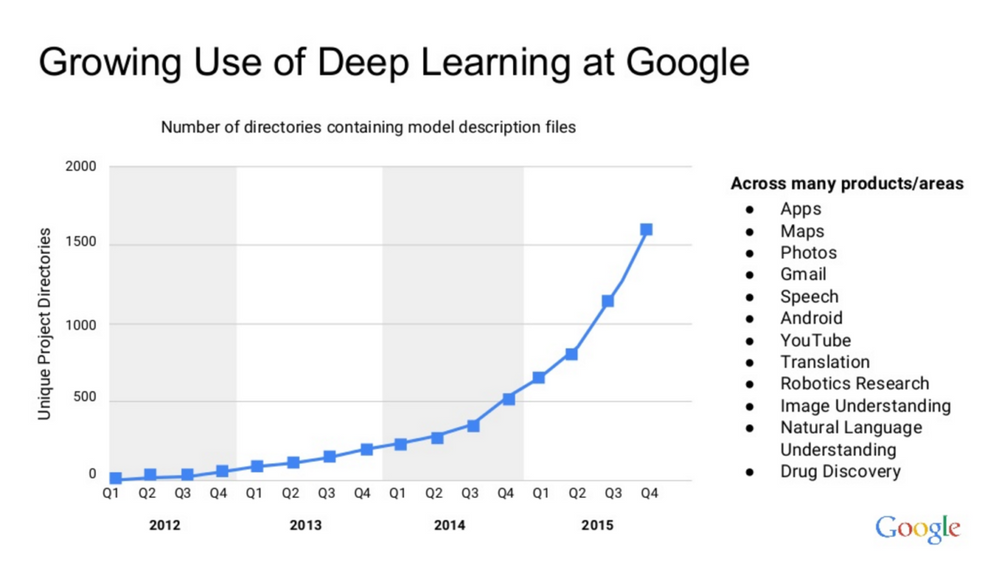

For some perspective on the extent of deep learning development, look at this graph from Google that shows the adoption of deep learning technology in their applications:

Source: https://www.slideshare.net/HadoopSummit/machine-intelligence-at-google-scale-tensorflow

As you can see, the adoption at Google has been exponential and the statistics are likely similar for many of the other big Internet firms like Facebook and Microsoft.

When Google embarked on converting their natural language translation software into using deep learning, they were surprised to discover major gains. This was best described in a recent article published in the New York Times, “The Great AI Awakening” [LEW]:

The neural system, on the English-French language pair, showed an improvement over the old system of seven points. Hughes told Schuster’s team they hadn’t had even half as strong an improvement in their own system in the last four years. To be sure this wasn’t some fluke in the metric, they also turned to their pool of human contractors to do a side-by-side comparison. The user-perception scores, in which sample sentences were graded from zero to six, showed an average improvement of 0.4 — roughly equivalent to the aggregate gains of the old system over its entire lifetime of development. In mid-March, Hughes sent his team an email. All projects on the old system were to be suspended immediately.

Let’s pause to recognize what happened at Google.

Since its inception, Google has used every type of AI or machine learning technology imaginable. In spite of this, their average gain for improvement per year was only 0.4%. In Google’s first implementation, the improvement due to DL was 7 percentage points better.

This translates to more gains than the entire lifetime of improvements!

Google likely has the most talented AI and algorithm developers on the planet. However, several years of handcrafted development could not hold a candle to a single initial deep learning implementation.

Deep Learning is unexpectedly, and disruptively, taking over the world

Google’s founder Sergey Brin, an extremely talented computer scientist himself, stated in a recent World Economic Forum [CHA] discussion that he did not foresee deep learning:

“The revolution in deep nets has been very profound, it definitely surprised me, even though I was sitting right there.”

The deep learning progress has been taking the academic community by storm. Two articles by practitioners of classical machine learning have summarized why they think DL is taking over the world. Chris Manning, a renowned expert in NLP, writes about the “Deep learning Tsunami“ [MAN]:

Deep learning waves have lapped at the shores of computational linguistics for several years now, but 2015 seems like the year when the full force of the tsunami hit the major Natural Language Processing (NLP) conferences. However, some pundits are predicting that the final damage will be even worse.

The same sentiment is expressed by Nicholas Paragios, who works in the field of computer vision. Paragios writes in “Computer Vision Research: the Deep Depression“ [PAR]:

It might be simply because deep learning on highly complex, hugely determined in terms of degrees of freedom graphs once endowed with massive amount of annotated data and unthinkable — until very recently — computing power can solve all computer vision problems. If this is the case, well it is simply a matter of time that industry (which seems to be already the case) takes over, research in computer vision becomes a marginal academic objective and the field follows the path of computer graphics (in terms of activity and volume of academic research).

Although I don’t want to detail the many deep learning developments of the past several years, Nell Watson provides a quick, short summary when she writes in “Artificial Intuition” [WAT]:

To sum up, machine intelligence can do a lot of creative things; it can mash up existing content [SHO], reframe it to fit a new context [PARK], fill in gaps in an appropriate fashion [CON], or generate potential solutions given a range of parameters [AUTO].

Make no mistake – Deep Learning is a “Disruptive” technology that is taking over operations of the most advanced technology companies in the world.

On Disruptiveness

Of late, the business world has become much more difficult and competitive. This situation has been made worse by disruptive changes in the global economy. The potential of nimbler competitors to disrupt the businesses of incumbents has never been greater. Peter Diamandis describes the Six D’s of Exponentials as consisting of the following:

- Digitization – Anything that can be digitized can lead to the same exponential growth we find in computing. Anything that is digitized or virtualized instead is unencumbered by physical law. It thus costs less to mass produce and moves faster in spreading.

- Deception – Once digitized or virtualized, initial growth deceptively appears linear. However, given time, exponential growth becomes obvious. For many it is too late to react once growth of a competitor hits this transition.

- Disruption – New markets that are more effective and less costly are created. Existing markets that are tied to the physical world will eventually become extinct. We’ve seen this in music, photography and many other areas.

- Demonetization – As cost heads towards zero, so does the ability to solicit a payment for it. Thus, a business has to reinvent its revenue model, or come up with new ways of monetization.

- Dematerialization – Physical products disappear and are replaced by a more convenient and accessible alternative.

- Democratization — More people now have access to technology at a lower cost. The means of production have become more accessible to everyone. This access is no longer confined to the big corporation, or the wealthy. We see this fragmentation everywhere where producers are publishing their own books, music and videos. This feeds back into itself and smaller players become able to compete.

To survive this disruption, there is an ever-pressing need for enterprises to take drastic action by re-engineering how they run their businesses.

John Hagel proposes four kinds of platforms [HAG] that leverage networking effects as an organizational mechanism to combat disruptive technologies. The four platforms that Hagel proposes are Aggregation platforms (example: Marketplaces), Social platforms (example: Social Networks), Mobilization platforms (example: Complex supply chains) and Learning platforms.

Learning platforms

Learning platforms are dynamic and adaptive environments where people come together to collectively learn how to address complex problems. Members can connect to ask questions, share experiences and offer advice. Open source projects that are actively managed with distributed source control, test-driven development, issue tracking, and continuous integration, is a good example of a learning platform. The key ingredient here is that there is a learning mechanism that gets codified continuously. The fact that we find this in software development should not come as a surprise, as software development is essentially a learning process.

John Hagel describes an intriguing property of a Learning platform:

What if we change the assumption, though? What if each fax machine acquired more features and functions as it connected with more fax machines? What if its features multiplied at a faster rate as more fax machines joined the network? Now, we’d have a second level of network effect — we’d still have the network effects that come by simply increasing the number of fax machines, but now there’s an additional network effect that accrues as each fax machine adds more and more features as a result of interacting with other fax machines.

What Hagel is saying is that the members of the network adaptively become more effective and capable as a participant in the learning network. In other words, not only is there the conventional networking effect, but another mechanism kicks network effects into overdrive. Learning platforms such as an open source community can further accelerate the disruptiveness of an already disruptive technology.

Historically, an open source strategy has been quite effective in many disruptive technology areas. In the Internet, Linux (79%) dominates in back end infrastructure services – Google’s Chrome (58%), Android (65%), Web-servers (65% Apache and Nginx). It should not surprise anyone when an open source strategy in the disruptive deep learning space eventually emerges as the dominant platform.

There are only a few semiconductor manufacturers that have the economies of scale to be competitive in high-performance computing. These are Nvidia, Intel, AMD, Qualcomm and Xilinx. We will now explore AMD’s deep learning solution and detail their unique open source strategy. We will also look at how it gives the company a competitive advantage.

Deep learning as a disruptive technology is critically enabled by hardware. AMD is one of the few semiconductor companies that actually exploits neural network in their hardware. In AMD’s SenseMI Infinity Fabric, an evolution of AMD HyperTransport interconnect technology, the design uses “perceptrons” to support branch prediction. AMD’s GPU hardware has always been competitive against Nvidia hardware. When algorithms are extensively optimized, AMD hardware is in fact favored. This is shown in the many cryptocurrency proof-of-work algorithms that have favored AMD hardware. Raja Koduri, head of AMD Radeon products, recently noted that AMD has had more compute per buck since 2005.

AMD’s Open Source Deep Learning Stack

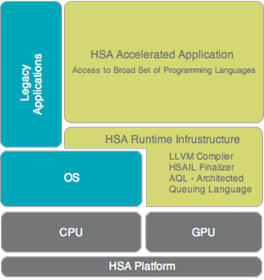

Before we get into the detail of AMD’s deep learning stack, let’s look at the philosophy behind the development tooling. AMD, having a unique position of being both a CPU and GPU vendor, has been promoting the concept of a Heterogeneous System Architecture (HSA) for a number of years. Unlike most development tools from other vendors, AMD’s tooling is designed to support both their x86 based CPU and their GPU. AMD shares the HSA design and implementations in the HSA foundation (founded in 2012), a non-profit organization that has members including other CPU vendors like ARM, Qualcomm and Samsung.

The HSA foundation has an informative graphic that illustrates the HSA stack:

As you can see, the middleware (i.e. HSA Runtime Infrastructure) provides an abstraction layer between the different kinds of compute devices that reside in a single system. One can think of this as a virtual machine that allows the same program to be run on both a CPU and a GPU.

In November 2015, AMD announced the ROCm initiative to support High Performance Computing (HPC) workloads, and to provide an alternative to Nvidia’s CUDA platform. The initiative released an open source 64-bit Linux driver (known as the ROCk Kernel Driver) and an extended (i.e. non-standard) HSA runtime (known as the ROCr Runtime). ROCm also inherits previous HSA innovations such as AQL packets, user-mode queues and context-switching.

ROCm also released a C/C++ compiler called the Heterogeneous Compute Compiler (HCC) targeted to support HPC applications. HCC is based on the open-source LLVM compiler infrastructure project [WIKI]. There are many other open source versions of languages that use LLVM. Some examples are Ada, C#, Delphi, Fortran, Haskell, Java bytecode, Julia, Lua, Objective-C, Python, R, Ruby, Rust, and Swift. This rich ecosystem opens the possibility of alternative languages on the ROCm platform. One promising development of this kind is the Python implementation called NUMBA.

Added to the compiler is an API called HC which provides additional control over synchronization, data movement and memory allocation. HCC supports other parallel programming APIs, but to avoid further confusion, I will not mention them here.

The HCC compiler is based on work at the HSA foundation. This allows CPU and GPU code to be written in the same source file and supports capabilities such as a unified CPU-GPU memory space.

To further narrow the capability gap, the ROCm Initiative created a CUDA porting tool called HIP (let’s ignore what it stands for). HIP provides tooling that scans CUDA source code and converts it into corresponding HIP source code. HIP source code looks similar to CUDA code, but compiled HIP code can support both CUDA and AMD based GPU devices.

AMD took the Caffe framework with 55,000 lines of optimized CUDA code and applied their HIP tooling. 99.6% of the 55,000 lines of code was translated automatically. The remaining code took a week to complete by a single developer. Once ported, the HIP code performed as well as the original CUDA version.

HIP is not 100% compatible with CUDA, but it does provide a migration path for developers to support an alternative GPU platform. This is great for developers who already have a large CUDA code base.

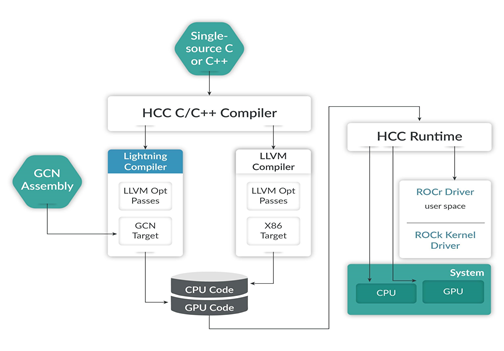

Early this year AMD decided to get even “closer to the metal” by announcing the “Lightning Compiler Initiative.” This HCC compiler now supports the direct generation of the Radeon GPU instruction set (known as GSN ISA) instead of HSAIL.

As we shall see later, directly targeting native GPU instructions is critical to get higher performance. All the libraries under ROCm support GSN ISA.

The diagram depicts the relationships between the ROCm components. The HCC compiler generates both the CPU and GPU code. It uses different LLVM back ends to generate x86 and GCN ISA code from a single C/C++ source. A GSN ISA assembler can also [1] be used as a source for the GCN target.

The CPU and GPU code are linked with the HCC runtime to form the application (compare this with HSA diagram). The application communicates with the ROCr driver that resides in user space in Linux. The ROCr driver uses a low latency mechanism (packet based AQL) to coordinate with the ROCk Kernel Driver.

This raises two key points about what is required for high-performance computation:

1. The ability to perform work at the assembly language level of a device.

2. The availability of highly optimized libraries.

In 2015, Peter Warden wrote, “Why GEMM is at the heart of deep learning” [WAR] about the importance of optimized matrix libraries. BLAS (Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms) are hand-optimized libraries that trace their origins way back to Fortran code. Warden writes:

The Fortran world of scientific programmers has spent decades optimizing code to perform large matrix to matrix multiplications, and the benefits from the very regular patterns of memory access outweigh the wasteful storage costs.

This kind of attention to every detailed memory access is hard to replicate despite our advances in compiler technology. Warden went even further in 2017 when he wrote, “Why Deep learning Needs Assembler Hackers” [WAR2]:

I spend a large amount of my time worrying about instruction dependencies and all the other hardware details that we were supposed to be able to escape in the 21st century.

Despite being a very recent technology, software that enables deep learning is a complex stack. A common perception is that most deep learning frameworks (i.e. TensorFlow, Torch, Caffe etc) are open source. These frameworks are however built on highly optimized kernels that are often proprietary. Developers can go to great lengths to squeeze every ounce of performance from their hardware.

As an example, Scott Gray of Nervana systems had to reverse engineer Nvidia’s instruction set [GRAY] to create an assembler:

I basically came to the conclusion that it was not possible to fully utilize the hardware I bought with the tools Nvidia provides. Nvidia, unfortunately, doesn’t believe in eating their own dog food and they hand assemble their library routines, rather than use ptxas like the rest of us have to.

Gray used assembly language to write their kernels, thus creating algorithms that bested the proprietary alternatives. Now imagine how much less work he would have to do if the assembly language was available and documented. This is what AMD is bringing to the table.

The ROCm initiative provides the handcrafted libraries and assembly language tooling that will allow developers to extract every ounce of performance from AMD hardware. This includes a rocBLAS [KNOX], an implementation of BLAS that provides these level capabilities:

BLAS Level-1:

- amax, amin, asum, axpy, copy, dot, nrm2, scal, swap

BLAS Level-2:

- gemv

BLAS Level-3:

- gemm, trtri, batched-trtri

This is implemented from scratch with a HIP interface. AMD has even provided a tool (i.e. Tensile) that supports the benchmarking of rocBLAS. AMD also provides an FFT library called rocFFT that is also written with HIP interfaces.

I wonder if Facebook’s fbcunn (Deep learning extensions for CUDA) [GIT], a library that employs FFTs to accelerate convolutions, could be ported using the HIP tooling.

Deep learning algorithms continue to evolve at a rapid pace. In the beginning, frameworks exploited the available matrix multiplication libraries. These finely tuned algorithms have been developed over decades. As research continued, newer kinds of algorithms were proposed.

Thus came the need to go beyond generic matrix multiplication. Convolutional networks came along and this resulted in even more innovative algorithms. Today, many of these algorithms are crafted by hand using assembly language.

Here is a partial list of deep learning specific optimizations that are performed by a proprietary library:

Activation Functions: ReLU, Sigmoid, Tanh, Pooling, Softmax, Log Softmax

Higher Order Tensor Operations: Ordering, Striding, Padding, Subregions

Forward and Backward Convolutions: 2D, FFT, Tiled, 3×3

Small Data Types: FP16, Half2

Normalization: Batch, Local Response

Recurrent Neural Network: LSTM

These low-level tweaks can lead to remarkable performance improvements. For some operations (i.e. batch normalization), the performance increases 14 times compared to a non-optimized solution.

AMD is set to release a library called miOpen that includes handcrafted optimizations. This library includes Radeon GPU-specific optimizations for operations and will likely include many of those described above. MiOpen is scheduled for a release in the first half of this year. Its release will coincide with the release of other popular deep learning frameworks such as Caffe, Torch7, and TensorFlow. This will allow application code that uses these frameworks to perform competitively on Radeon GPU hardware.

Many other state-of-the-art methods have not yet worked their way into proprietary deep learning libraries. These are proposed almost every day as new papers are published in Arxiv.

Here are just a few:

- CReLU

- PReLU

- Hierarchical Softmax

- Adaptive Softmax

- Layer Normalization

- Weight Normalization

- Wasserstein Loss

- Z-Loss

It would be very difficult for any vendor to keep up with such a furious pace. In the current situation, given the lack of transparency in development tools, developers are forced to wait, although they would rather be performing the coding and optimizations themselves. Fortunately, the open source ROCm initiative solves the problem.

ROCm includes an open source GCN ISA based assembler and disassembler.

System Wide Optimization

In a recent investor’s meeting by Intel, the company shared some of their statistics:

Among servers used for deep learning applications, the chipmaker says that 91% use just Intel Xeon processors to handle the computations, 7% use Xeon processors paired with graphics processing units, while 2% use alternative architectures altogether.

The mix will change as the value of deep learning is understood better. The point here is that CPUs will always be required, even if most of the computations are performed by GPUs. That being said, it is important to recognize that system-wide optimizations are equally critical. This is where AMD’s original investments in Heterogeneous System Architecture may pay big dividends. I would however like to point out that new research efforts are underway to optimize the code that is emitted by deep learning frameworks further.

Deep learning frameworks like Caffe and Tensorflow have internal computational graphs. These graphs specify the execution order of mathematical operations, similar to a dataflow. These frameworks use the graph to orchestrate its execution on groups of CPUs and GPUs. The execution is parallel and this is one reason why GPUs are ideal for this kind of computation. There are however plenty of untapped opportunities to improve the orchestration between the CPU and GPU.

The current state of Deep Learning frameworks is similar to the state before the creation of a common code generation backend like the LLVM. In the past, every programming language had its own way of generating machine code. With the development of LLVM, many languages now share the same backend code. The frontend code only needs to translate source code to an intermediate representation (IR). Deep Learning frameworks will eventually need a similar IR for Deep Learning solutions. The IR for Deep Learning is the computational graph.

New research is exploring ways to optimize the computational graph in a way that goes beyond just single device optimization and towards more global multi-device optimization.

An example of this is the research project XLA (Accelerated Linear Algebra) from the TensorFlow developers. XLA supports both Just in Time (JIT) or Ahead of Time (AOT) compilation. XLA is a high-level optimizer that performs its work by optimizing the interplay of the CPUs, GPUs and FPGAs.

The optimizations planned include:

- Fusing of pipelined operations

- Aggressive constant propagation

- Reduction of storage buffers

- Fusing of low-level operators

There are two other open source projects that are also exploring computational graph optimization. NNVM from the MXNet developer is another computation graph optimization framework that, similar to XLA, provides an intermediate representation. The goal is for optimizers to reduce memory and device allocation, while preserving the original computational semantics.

NGraph from Intel is exploring optimizations that include:

- Kernel fusion

- Buffer allocation

- Training optimizations

- Inference optimizations

- Data layout

- Distributed training

There are certainly plenty of ideas around of how to improve the performance.

AMD has developed a runtime framework that takes into account heterogeneous CPU-GPU systems. It is called Asynchronous Task and Memory Interface (ATMI). The ATMI runtime is driven by a declarative description of high-level tasks that will execute the scheduling and memory in an optimal manner.

ATMI is also open source and can be exploited to drive deep learning based computational graphs like the ones found in XLA, NNVM or NGraph. The future of Deep Learning software will revolve around a common computational graph and optimizations will take the orchestration of the entire system into consideration.

Operations and Virtualization

What we have been discussing so far are the opportunities to squeeze as much performance from hardware as possible, but there is more to a complete solution than just raw performance.

Every complex system requires good manageability to ensure continued and sustained operations. The ROCm initiative does not overlook this need and provides open source implementations. ROC-smi, ROCm-Docker and ROCm-profiler are three open source projects that provide support for operations.

AMD’s GPU hardware and drivers have also been designed to support GPU virtualization (see: MxGPU). This permits GPU hardware to be shared by multiple users. I will discuss operational aspects of AMD’s offerings in a next article.

Deployment

Throughout this article, we’ve discussed the promising aspects of the ROCm software stack. When the rubber meets the road, we need to discuss the kind of hardware that software will run on. There are many different scenarios where it makes sense to deploy deep learning. Contrary to popular belief, not everything needs to reside in the cloud. Self-driving cars or universal translation devices need to operate without connectivity.

Deep learning also has two primary modes of operation – “training” and “inference”. In the training mode, you would like to have the biggest, fastest GPUs on the planet and you want many of them. In inference mode, you still want fast, but the emphasis is on economic power consumption. We don’t want to drive our businesses to the ground by paying for expensive power.

In summary, you want a variety of hardware that operates in different contexts. That’s where AMD is in good position. AMD has recently announced some pretty impressive hardware that’s geared toward deep learning workloads. The product is called Radeon Instinct and it consists of several GPU cards: the MI6, MI8, and MI25. The number roughly corresponds to the number of operations the card can crank out. An MI6 can perform roughly 6 trillion floating-point operations per second (aka teraflops).

The Radeon Instinct MI6 with a planned 16GB for GDDR5 memory is a low-cost inference and training solution. MI8 with 4GB HBM is designed primarily for inference-based workloads. MI25 is designed for large training workloads and will be based on the soon to be released Vega architecture. Shuttling data back and forth between GPU and CPU is one of the bottlenecks in training deep learning systems. Vega’s unique architecture, capable of addressing 512TB of memory, gives it a distinct advantage.

There’s also a lot more to say about GPU and CPU integration. I’ll briefly mention some points. On the server-side, AMD has partnered with Supermicro and Inventec to come up with some impressive hardware. At the top of the line, the Inventec K888 (dubbed “Falconwitch”) is a 400-teraflop 4U monster. By comparison, the Nvidia flagship DGX-1 3U server can muster a mere 170 teraflops.

There is also promise at the embedded device level. AMD already supports custom CPU-GPU chips for Microsoft’s Xbox and Sony’s PlayStation. An AMD APU (i.e. CPUs with integrated GPUs) can also provide solutions for smaller form factor devices. The beauty of AMD’s strategy is that the same HSA based architecture is available for the developer in the smallest of footprints, as well as in the fastest servers. This breadth of hardware offerings allows deep learning developers a wealth of flexibility in deploying their solutions. Deep learning is progressing at breakneck speed and one can never predict the best way to deploy a solution.

Conclusion

Deep learning is a disruptive technology like the Internet and mobile computing that came before. Open source software has been the dominant platform that has enabled these technologies.

AMD combines these powerful principles with its open source ROCm initiative. On its own, this definitely has the potential of accelerating deep learning development. ROCm provides a comprehensive set of components that address the high performance computing needs, such as providing tools that are closer to the metal. These include hand-tuned libraries and support for assembly language tooling.

Future deep learning software will demand even greater optimizations that span many kinds of computing cores. In my view, AMD’s strategic vision of investing heavily in heterogeneous system architectures gives their platform a distinct edge.

AMD’s open source strategy is uniquely positioned to disrupt and take the lead in future deep learning developments.

Carlos E. Perez is Co-Founder at Intuition Machine. He specializes in Deep Learning patterns, methodology and strategy. Many of his other writings on Artificial Intelligence can be found on Medium. His postings are his own opinions and may not represent AMD’s positions, strategies, or opinions. Links to third party sites and references to third party trademarks are provided for convenience and illustrative purposes only. Unless explicitly stated, AMD is not responsible for the contents of such links, and no third party endorsement of AMD or any of its products is implied.

FOOTNOTES:

[AUTO] Autodesk. http://www.autodesk.com/solutions/generative-design

[CHA] Chainey, Ross. “Google co-founder Sergey Brin: I didn’t see AI coming.” https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/google-sergey-brin-i-didn-t-see-ai-coming/

[CON] Conner-Simons, Adam. “Artificial intelligence produces realistic sounds that fool humans.”

http://news.mit.edu/2016/06/13/artificial-intelligence-produces-realistic-sounds-0613

[GIT] Facebook FAIR. https://github.com/2017/facebook/fbcunn

[GRAY] Gray, Scott. “Maxas Assembler.” https://github.com/NervanaSystems/2015/01/24/maxas/wiki/Introduction

[HAG] Hagel, John. “Harnessing the Full Potential of platforms.” http://www.marketingjournal.org/2016/04/05/john-hagel-harnessing-the-full-potential-of-platforms/

[HSA] “HSA-Debugger-AMD.”

https://github.com/HSAFoundation/2015/12/24/HSA-Debugger-AMD/blob/master/TUTORIAL.md

[KHAT] Khatchadourian, Raffi. "The Doomsday Invention." http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/11/23/doomsday-invention-artificial-intelligence-nick-bostrom

[KNOX] Knox, Kent. “rocBLAS.” https://github.com/RadeonOpenCompute/2016/11/09/rocBLAS/wiki

[LEW] Lewis-Kraus, Gideon. “The Great A.I Awakening.” https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/14/magazine/the-great-ai-awakening.html?_r=1

[MAN] Manning, Christopher. “Computational Linguistics and Deep Learning.” http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/2016/06/10.1162/COLI_a_00239

[PAR] Paragios, Nikos. “Computer Vision Research: ‘The deep depression.’”

https://www.linkedin.com/2016/06/05/pulse/computer-vision-research-my-deep-depression-nikos-paragios

[PARK] Parkinson, Hannah Jane. “Computer algorithm recreates Van Gogh painting in one hour.”

[SHO] Shontell, Alyson. “A start up that uses robots to write news gets acquired for $80 million in cash.” http://www.businessinsider.com/2015/02/23automated-insights-gets-acquired-by-vista-for-80-million-20...

[WAR] Warden, Pete. “Why GEMM is at the heart of deep learning.” https://petewarden.com/2015/04/20/why-gemm-is-at-the-heart-of-deep-learning/

[WAR2] Warden, Pete. “Why Deep Learning Needs Assembly Hackers.” https://petewarden.com/2017/01/03/why-deep-learning-needs-assembler-hackers/

[WAT] Watson, Nell. “Artificial Intuition; The Limitations (and ridiculous power) of Deep Learning Creativity.” https://medium.com/intuitionmachine/artificial-intuition-/2017/03/-3418fac2eb9c#.wrr6unq5g